Embrace It with Lainie & Estela - Smashing Disability Stigmas

Embrace It with Lainie & Estela - Smashing Disability Stigmas

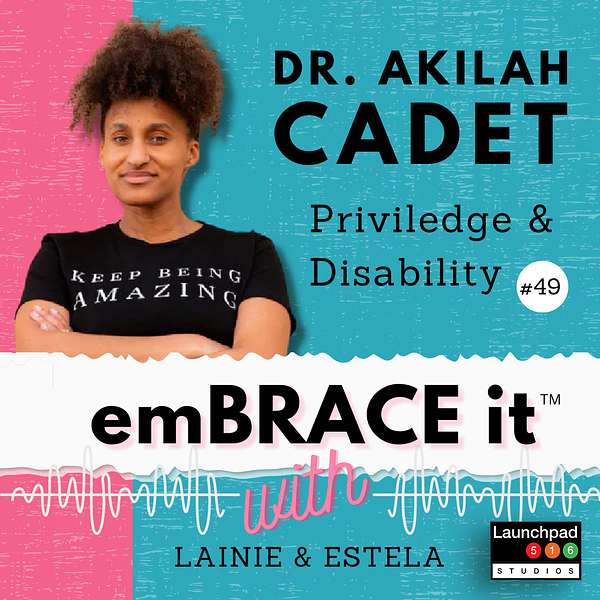

Embrace It: Episode 49 - Dr. Akilah Cadet, Privilege & Disability

In this episode, we're diving into how privilege can shape our access to healthcare and opportunities with the fabulous Dr. Akilah Cadet, who has spent an extensive part of her career designing training, coaching executives, and informing systematic change to improve the workforce experience for large organizations.

We’re shedding light on how many forms of privilege can act like a golden ticket affecting how easily we access medical care and career opportunities. Tune in to gain Dr. Cadet’s valuable insight and resources for patient advocacy and why privilege matters to us all.

- Visit Dr. Cadet’s Website

- Follow Dr. Cadet on Instagram

- Preorder Dr. Cadet’s Book

- Book an EmBRACE It Workshop

- Looking for more great tips, hacks, and blog posts? Visit: Trend-Able.com

- Find more on Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) and patient resources at: HNF-cure.org

- Follow us on IG! @embraceit_podcast | @trend.able | @cmtwegotthis

Please leave us a review and help others find us!

Hosted by Lainie Ishbia and Estela Lugo.

Embrace It is produced by Launchpad 516 Studios.

For sponsorships and media inquiries, drop an email to: embraceit@lp516.com

Subscribe to Embrace It with Lainie and Estela on Apple Podcasts and get notified of new episodes! https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/embrace-it-with-lainie-estela-smashing-disability-stigmas/id1468364898

Welcome to the Embrace it series, where women with all types of disabilities can be real, resourceful and stylish. With each episode, you'll walk or roll away with everyday tips, life hacks and success stories from community leaders and influencers. So take off your leg braces and stay a while with Lainey and Estella.

Speaker 1:Hi, I'm Lainey and I have CMT. I'm a neuro-muscular disorder affecting approximately 2.6 million people worldwide.

Speaker 3:That's as many as MS. We believe disabilities should never get in the way of looking or feeling good. Both of us wear leg braces and have learned through our own personal journeys to embrace it Brought to you by Launchpad 516 Studios.

Speaker 1:each episode is designed to challenge your own stigmas and beliefs around disability. We want our listeners to get the most value for their time spent with us, so we interview some of the most empowering disability badasses in the world. Through storytelling, personal experiences and tips, we're all reminded of our own strengths and endless potential.

Speaker 3:For more information and exclusive resources, check out our websites at trend-ablecom and hnf-curorg, and don't forget to hit the subscribe button for future episodes and special promos.

Speaker 1:Welcome everyone to another episode of the Embracing Podcast. Hey there, lainey, hi Estella, hey, we are so excited to be bringing a guest who actually we were connected to through another past guest, nidhika Chopra, who we had on not too long ago, who is telling us about Chronicon, and I was lucky enough to be a guest at Chronicon and then we came across an amazing panel with Dr Akila Kadei, who is today's guest. Welcome, dr Kadei, how are you? Thank?

Speaker 4:you. Hello, I'm good. Thank you for having me. Lainey and Estella, it was lovely to meet you in person too, which is still a new thing to meet people in person as we're coming out of the pandemic that's still here, but a little bit safer for folks. So great to be here.

Speaker 1:Yeah, so you're very young, you are still very accomplished and it's very impressive when we keep reading about your background here, just like we keep scrolling on and on and on because you've done so much in such a short amount of time. But you are the founder of Chronicon and maybe you could tell us a little bit of you know. You have an extensive background in healthcare. You have a doctorate in healthcare, I believe, as well. We'd love to know a little bit about what your personal journey is with disability and how you kind of navigated that as well as accomplishing all these incredible things.

Speaker 4:Yeah, so I'm the founder and CEO of Change Kadei. It's an organizational development consulting firm. We center in creating cultures and spaces of belonging. We do that with my lens of intersectionality, as a Black, disabled woman, and so we're advocating for our BIPOC, black and Indigenous, people of color women, lgbtq plus, disabled communities and how they show up in the workspace. A lot of people don't realize that we spend more time at work than we do in our lives. For most of us, we have to work in these nine to five spaces, so it's important that we have these spaces that can celebrate and value us, opposed to being tokenized or overlooked or othered. So we do that with companies all over the world, from small businesses to startups, all the way up to multi-billion dollar companies like Google. We work with tech, beauty, beverage, fashion, you name it. There's something that we have done or are currently doing that you use every day, and it's something that we're very proud of Along the way of doing all of this stuff, a year into being into my business full time.

Speaker 4:So I started changing today as a site household for about a year and I went into full time. My baby, my company, is eight years old. About a year into it. I started to have health problems and that led to diagnosis of rare conditions, rare disease. So I live with three rare diseases. I'm not trying to win the competition, but I feel like I should get a medal for that. So what people most know me for is that my body thinks it's having a heart attack every day. So the arteries in my heart close, they just close. My heart is beautiful structurally, it's so pretty solid, but my arteries just close. So I live with the symptoms of a heart attack. So shortness of breath, I will have pain in my left arm, I'll have pain in my chest and then I also have so it's called coronary artery spasms. I also have Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. So Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is a rare disease. It's a connective tissue disease. I mean my body doesn't make enough collagen. Collagen is in everything. So I have tight muscles, loose muscles, I have joints that dislocate, I have joints that subluxate, go in and out. I have a lot of comorbidities because, again, organs need collagen and things can happen as a result of that.

Speaker 4:Prior to chatting with you today, I was on the floor because I have orthostatic hypertension and my blood pressure dropped really low. So my team meeting, I was on the floor for my team meeting so I could do this for you and sit up, and I'll go back on the floor after this. But so I say that because when we put together creating cultures of belonging and coming into building my business as a black person, as a woman, and the intersectionality was there along the way, disability came into the mix, and so I didn't choose to be a disability advocate. I chose to value my life. So there's a difference. So I say things and I do things. I also realized that I'm cute AF. I'm pretty.

Speaker 4:I don't look disabled. I don't look like I have chronic pain or chronic illness. I live with visible and invisible disability, depending on how my body shows up. Maybe I have a cane, maybe I don't. Maybe I have a bracelet, maybe I don't. So I realized that I have the power and privilege to use all of what has been given to me to help people think differently. If they see or hear that I have a disability, maybe they can have some softness moving forward with other people. As I advocate for a being a woman or being a black person, maybe they can have some softness, compassion, understanding, moving forward. And so I use that trifecta with how I show up and do that work.

Speaker 4:And all of that is tied to the fact that I happen to have too many degrees. So my undergrad is in health science, community-based public health. I have a master's in public health and my doctor is in health science and leadership and organizational behavior, so I understand people, systems, leaders and also healthcare and how health is delivered. So, as a patient advocate for myself, I was telling people what they need to do because I had that insider experience of being a health administrator and working in health and public health for so long, so I started to share that. And then, voila, I'm an advocate. So that's the long story.

Speaker 3:Akila, you are so accomplished and, to reiterate, estella, you're young and accomplished. But what's amazing to me, as I kind of looked at some of this work you've done and the stuff you've done and heard you on other podcasts, it sounds like your family was very much an act. Your mom was an activist herself and so you came by it rightly. But what's interesting to me, which I didn't know, is that your disabilities, your chronic conditions, didn't come until pretty recently. So you already were an activist about gender and race and, I'm assuming, disability.

Speaker 3:But how did your own diagnosis like? How did that shift the you know the film of what you're focusing on, because so many of us are in that DEI right, community and disability is left out. Like that's the theme I hear. Absolutely, and that's what disability advocates always say is that when companies like Google and those big companies you work with, when they think about DEI, they're not thinking about disability, they're thinking about LGBTQ, they're thinking about race and on him. So yeah, okay, that was a lot, but you hear me right, like you already were an activist.

Speaker 3:You already were a hot button for a lot of issues, like you already were. You have a platform. You already was out there, and then you yourself. You know and I also, by the way my disabilities are mostly invisible as well, and you know how did that go?

Speaker 4:Yeah, you have all that. You confuse people all the time. I know Right it's so it's so fun.

Speaker 3:Well, it's cool because it's like a breaking of stereotypes on my end. Right, and I'm not in comparison people, we're not comparing. But I do not have like a chronic illness. You know, I'm pretty much the same. You know, most days I have I wear like braces, I have a physical you know, physical disability. So I'm some emotional. I mean that's the best days. Yeah, that's the best thing I think, to show. Okay, Back to you. Tell us how that you know diagnoses like influenced the work that you do.

Speaker 4:Yeah, I mean I transfer skillset because I already had to advocate for myself as a woman, as a black person, as a young person and leadership positions as someone. I got my doctor and I was 33. So you know that isn't not that people don't do that, but it's not typical to do that. But I got my doctorate because I knew that even if people didn't value or respect me as a black person or as a woman, they still had to call me doctor today and I love that.

Speaker 4:It's so much joy, right. So they have to do the math and like, okay, well, at least she committed to this time and investment to do this thing. And so, when it came to disability, I had to work through feelings and emotions of what disability meant. I have absolutely no problem being disabled.

Speaker 4:I have a problem with how society views disabled people. So, for example, I'll say sometimes in talks like do I look disabled? And people are like no, I'm like, we'll see. This is the problem, because disability looks more than one way.

Speaker 4:You were thinking disability is maybe a wheelchair, because the sign is always a wheelchair, which is why I've been discriminated against because I don't have a wheelchair. Right, you think it's someone who looks older or they have some type of what you may view as a deformity to be disabled. It doesn't look like me. But societal standards has said you can't be independent, you can't be successful, you can't be smart, you can't be beautiful, you can't be these things and be disabled. That doesn't make any sense. So you must just be entitled, because that fits into the stereotype of thing when I'm asking for accommodation, when I'm preboarding on a plane or whatever the thing may be.

Speaker 4:And so I had to go through the emotions of realizing that my life would be forever changed Because people wouldn't believe me, people wouldn't value me, people wouldn't want to provide accommodations, people hear disability and maybe they wouldn't want to date me. All of these things because I did not. And still it's harder. It's getting better to see positive influences of disabled people, representative media and positions of power. A lot of people will hide these things.

Speaker 4:I hid it for a year while I was trying to figure out. My stuff started with my heart and so I was like clearly it's going to be fixed because I'm a vegetarian, I don't have heart history issues myself or within my family. When I realized it was forever, I did what people do nowadays, which is post on Instagram. I was like, hey, how are we doing? This is part of me and I know what this is going to mean for how people are going to view me. But I would be doing a disservice to how I was advocating for myself previously if I wasn't embracing the fact that I was disabled and accepting what would come along with it. I have to accept racism, I have to accept sexism and discrimination that comes along with it.

Speaker 4:So come on in Abelism come into the fun Then putting it back into my position of power and privilege that I've been able to build so that I can't even talk and role model about it. Now the interesting thing with my disability is that my disability anniversaries next month will be six years that I've officially been disabled, because it took a while to get to diagnosis and then once I knew it. So I always buy myself something very big, something very shiny, usually a diamond when that happens and because it's a big deal to live another year with all the stuff that I have to live with.

Speaker 3:It's like a push present that President Obama totally deserves right.

Speaker 4:We push through healthcare system discrimination, abelism, racism, what I have I've had my whole life, but things started to come later in life. So all of these things are genetic. So, as particularly with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, as I look back on my life I was like, oh, that was not a basketball injury, that was a subluxation, that was a full dislocation, that was like my ankle going a trip and my ankle would be swollen and I'd have to wrap it up. For whatever. All of this stuff, it made sense. Oh, the incision didn't heal. Like these things. I'm like, oh, I've had this all my life.

Speaker 4:So the other side of disability is realizing that some people are born with disability and it's a different life. Some people are disabled later on in life because of later diagnosis, genetics, injury, accident, whatever it may be. So I'm new on my disability journey and so I'm continually figuring out what that means. But once I did that Instagram post, I realized that it is, in fact, a source of pride and that was the start of how I would educate myself and learn so I can be a better advocate for people who are disabled.

Speaker 1:I love that because we're all on our own journey and, like you said, some of us have been. Even if we've been living with it our entire lives, it still presents itself in new situations every day and we're constantly having to evolve. You touched upon privilege and I think the panel that you were on at Chronicon was really interesting to me because it really highlighted the different types of privilege that I think, depending on you know our personal experience, we're not aware of what those points of privilege are, how we can go about identifying them, how we can be allies to others who don't have those privileges that we have, and also, especially, in the way of advocating for ourselves, for our medical care. Can you you know, as someone who has this knowledge and this expertise in the healthcare system, what were some of the things that you discovered during your personal journey seeking medical care and what are some gems and words of wisdom you could share with some of our listeners who might be struggling with that right now?

Speaker 3:And and definitely the privilege part, because like you said that. But what does that mean?

Speaker 4:Right.

Speaker 3:Like, does that mean money? I think of privilege and I think of someone who's well off work can afford medical care. So you go ahead Totally.

Speaker 4:So we talked about privilege that's earned and unearned, so un-urned. Privilege is granted to anyone, regardless of whether they want that or not, like it's. Think about it in the words of Lady Gaga born this way, how did you come into this world? Are you a white guy? You have more privilege. Did you come from money? Did you grow up in a middle class or upper class neighborhood? Did you have both your parents? Right, like, because that's a different type of life and trajectory that individual is going to have, regardless of how they identify.

Speaker 4:When we think about the privilege pyramid, if you will, the person who has the most powers the heterosexual, cisgender, non-disabled white man. Do you have a heterosexual, cisgender, disabled white man? Less power because we're deemed as unworthy as disabled people. We are in a press group because we're not perfect the best and that's a tenant of white supremacy. So there's that. So you have an un-unprivileged, but we also have earned privilege.

Speaker 4:So what were people able to acquire over time themselves? Right? Maybe it was built off of their un-unprivileged. So maybe they were able to get an undergrad degree, but they had to pay for their master's degree or their doctoral degree to get this additional level of privilege. Maybe you know the degree was paid for by parents or wealth or access to money, whatever that was, without being in debt. But they're the first woman to be in that program, right? Or they're the first woman to work at a big company, right, and have that afforded privilege, like if you, you know, if you work at Nike, you were set you can work anywhere, right? We know that there's these certain companies and brands. If you're there, then that changes your career and your trajectory. It changes your access that you may have. Maybe you want the lotto that's, you know, earned privilege. Now you have more money, right? Whatever that thing may be, there's a lot of things that are there, and so when you realize you have earned an un-unprivileged, that's how you know how you can move into the world.

Speaker 4:So I have un-unprivileged because I grew up in a middle-class neighborhood. I found the way I sound. Some people think I talk white, but I talk like an American because that's where I'm from, and maybe I sound smart because I have three degrees. So it makes sense right for that, you know. So those are some of the things that I offer un-unprivileged.

Speaker 4:When it comes to earned privilege, having a company, I had to do that myself. I had to finance that myself, my doctorate. I had to do that myself. You know, like these types of things I do for myself. But, as I mentioned earlier, because I have this doctor title, people believe what I have to say. It's a lot of power and a lot of privilege. As a result of that, 3% of people in the US have a doctoral level degree, and for black women it's like less than 1%. So I know I'm in a very privileged group. So that's setting the stage for privilege. So how do we use that? And you know how we show up in advocacy for ourselves.

Speaker 4:So because I worked in healthcare, because I went to my doctorate from a med school like I, you know, non-clinical. I'm a non-clinical person, I have a lot of tools. So when I go in and I meet a new provider I just met a new provider a couple of weeks ago she came in and was like hi, miss Kitty, and I said no, it's doctor. And then there's a question and I'll say I have a non-clinical degree, my doctorate is in blah, blah, blah and I was also formerly pre-med but I changed my major to be into administration. So I understand. So I'll set the expectation. I understand what you're going to tell me. If I don't, I will clearly ask you a question. I have a knowledge of myself, my body, and I set that right away. If they're defensive, usually never going to see them again. But if they understand that they'll be like oh great, thank you, we go there.

Speaker 4:If I have to go to the emergency room, I always have a doctor's note that's sent with me. It's usually my cardiologist, because it's usually when I have to go to the emergency room and we're besties because he values me and I value him and he has two doctorates and I have one and we have a lot in common and he always believed that I had a heart problem and so we've established this relationship where he sends a note ahead of time. So I'm further believed because I'm a black woman. So that means my pain is not believed as a black person. There's lots of data out there that shows that. So understanding your privilege, power, intersectionality or identity is really important to how you advocate for yourself. And I'm a woman, so my heart stuff is never believed, even though it's on my chart, even though there's a history of that. So women in cardiovascular health were viewed completely differently because we're stressed, you know, for being a woman.

Speaker 1:We have so much anxiety.

Speaker 4:It's so hard, yeah, yeah, it's so hard, right, and so that's why I have that note. It adds more fire on top of the fact that I'm also a colleague of that individual. That's a doctor. I understand that's additional privilege, but everyone can ask for a doctor's note in that scenario. Then it's important to know your patient rights. What are your patient rights? Wherever you live, you need to know them so you can use them. Also know who your patient advocate is within your healthcare system. They can figure stuff out for you. You don't have to necessarily do that. There's literal advocates. They're there. You just may do a little digging.

Speaker 3:Like in the hospitals you need, like you lay it out In your healthcare system.

Speaker 4:So, whether you're calling someone, there's advocacy programs, there's navigating, chronic illness things. There's social work that can come up from it. Social work is not just placement for someone who doesn't have access to a home or needs to be placed in a home. It's also for how you're advocating for yourself. There's that, but it's also how you're talking to the provider too. So if you've done your own research and a lot of us do, because we will research things we'll use Google as a search tool to figure out certain things. We'll ask questions, we'll go to conferences, we'll go to Chronicon to figure things out, as you're bringing these things up to your provider and your appointments obviously write things down. But if they're saying no, you probably don't have that or know we don't have to test for that. Here's what you say. Can you notate that in the chart, please? And once you say that they're like fine, I'll do it.

Speaker 4:And the reason is there can always be a risk that someone else in the same system does that test and they find something and that creates a potential liability for said doctor, and so you always want them to notate that If they don't do that, you can follow up. When you get your chart summary at the end of your appointment, you can follow up via email, because now it's a paper trail. Please notate that you don't want to do this test for this procedure or this examination, so I have it on record and usually they'll order the thing.

Speaker 1:Does that go for like something like genetic testing? I don't know if you know the specifics of that, because with the H&F we see that a lot where patients are coming to us through our genetic testing program because their doctors have denied it or kind of talked them out of it, so that's a larger systemic issue.

Speaker 4:That's a larger systemic issue. So geneticists and healthcare systems are far and few between, just get paid more being with a private company. So that's where they are. So people are paying out of pocket for that. So, for example, I'm part of UCSF, so University of California, san Francisco, for specialty care. I could not get into the genetics testing. I could not get in, so I had to pay for it out of pocket.

Speaker 4:And when I was able to get my test, to work with a geneticist to figure out an appropriate plan or be placed into a specialty care clinic, I was rejected because I went outside to get my testing done, which makes no sense. But the catch is 22, right, right, yeah, but that genetics testing I've used with my providers that I already am in care with, and so I had to do my own care. So instead of me going to, like the Ellersdano's you know the center to get wrap around care, multidisciplinary care, because with EDS we don't have a provider, we don't have a gastroenterologist. We may have a gastroenterologist, but that's not the person who solves it. We have it's a multidisciplinary focus for EDS, right? So instead of having someone do that for me and centralize, I have to do it for myself, but I could have waited maybe another year. I did all the steps and appointments I had to do to get reports and everything, but I didn't want to suffer. And I have the privilege to pay for genetic testing, which is not expensive. You know, depending on the person, you can save up for the 200 bucks or 150 bucks or 80, but whatever it was. But I chose to do that so I can get better care and better pay management. But that doesn't work within the systems. So that's the last thing.

Speaker 4:Healthcare is designed for profitability. It is not designed for you to thrive. It's not designed for you to be well, it's designed for you to be unwell. So you know, when you know that, you realize like, well, how can I advocate for myself? What are the structures and systems that are in place? What resources can I use? Who in my family or friends or chosen family can come to me with an appointment or be willing to help schedule appointments for you?

Speaker 4:Whatever you need to do for your capacity to get that done, I feel one of the worst things in America is that as a patient, you also have to be an advocate. So you can't even heal right, so I can't have stress. If I have stress I can have heart attack. So I live with the symptoms of a heart attack, but I can have a heart attack at any moment in time. I could die at any moment in time. Boom, just like that. So I have to be as chill as possible. But when I can't get an appointment or someone's not calling me back or heaven forbid something has to be faxed.

Speaker 3:Right isn't that crazy. I know those like 2023.

Speaker 1:2023, something is faxed Well, don't you?

Speaker 3:have online, can't I? I don't understand, I can't. Just, you know, email. I can't use any other form but snail mail or fax, electronic records.

Speaker 4:Yeah, and I'm like, okay, it's a funny thing. I was at an appointment and they could see the imaging, but now all of a sudden you can't see the imaging. I was recently in the emergency room, last month, because that's where I like to hang out, you know every time I go there I'm like, maybe I'll find my husband.

Speaker 4:I've never found my husband, I had to consult a vascular surgeon and so I was given a referral from the health system that I was in for emergency care, and then another referral, so for one health system and another referral for UCSF. I call the UCSF. They're like we won't see you. We need a referral, we need all these things, we know, and we will call you and we are gonna call you, but you actually have to call us back. I don't know if we're gonna get it faxed, something, something or another.

Speaker 4:I call the other one to set our health, the system I'm part of, and they're like when I say the same thing, I just was discharged from emergency room. These things are happening for my imaging. I need to consult a vascular surgeon and they're like yeah, sure, no problem, we see that. Yep, well, can you come next week? Do you need a referral? Nope, that's us, that's for us to take care of. We'll see you next week, okay, well, can I fly? I'm supposed to fly in two days. Hold on, let me ask the doctor. Yes, you can fly right, and that is an example of how fucked up healthcare is right and how that works. So imagine navigating that over and over again. This is why some people don't get the care that they need because they don't have the time and energy to invest in what's needed to advocate for themselves to be well.

Speaker 3:Or to be better and like as you started the whole thing. With unearned I mean obviously in a lot of cases unearned privilege leads people to earned privilege, right.

Speaker 3:You no one helped you maybe start your business, but because of your unearned privilege of growing up in a middle class neighborhood and being exposed to people who had their own businesses and were successful or not successful, you then felt you could. It's impossible. A lot of people don't feel like their voice matters. So like and so like people who are listening to us right now. You guys know that Estelle and I do a lot of work with help with people, like finding their voice and teaching people assertiveness skills as it relates to disability. Like talking about what you have, feeling comfortable, have comebacks to when people say things and it triggers your anger or sensitivity or feelings of need to withdraw, Like having tools. What you're saying really is that you have a PhD, I mean you're smart.

Speaker 3:There's so many people who you know, having nothing to do with education, but literally with their own sense of like, respecting doctors, like they think the doctor knows so they just let them handle the decision, like the old school way of like our parents, parents like they believe, like every doctor. There wasn't WebMT, there weren't things to Google. People who don't have privilege may not have access to big mouths, like Laini, ishvia, like, who are like you should advocate for yourself. Make sure to write everything down, make sure to tape it. Don't trust it. There's no one coordinating. Get a second, I'm not paying it. Yeah, there is no. The olden days of your internist coordinating things is done. People, you know you have to have a very special internist, like because they don't even have hospital privileges anymore, like a lot of them are. No one is seeing what the other is doing, so it takes a smart individual yourself usually to track everything and you know I don't know. It's exhausting.

Speaker 3:I mean it's exhausting just thinking about yeah.

Speaker 1:Yeah, and that's the reason you know patients come to us. They're completely overwhelmed. We'll be right back.

Speaker 6:This is George, fred and Jason, the co-leaders of Speak, interrupting to say that we hope you're enjoying this episode, but please make sure to check out our new show, the Speak Podcast, another great show produced by Launchpad 516 Studios. New episodes available every week on all of your favorite podcast platforms.

Speaker 5:Each Speak Talk is about six to 10 minutes in length, and the talks are given in storytelling format. There are three key moments in each Speak Talk the moment of truth, the moment of transformation and the moment of impact. We host pop-up events all over the world, and now we're bringing our talks to your device.

Speaker 6:Join us on the Speak Podcast as our speakers step onto the stage and into the spotlight with impactful ideas and stories. We'll let you get back to the show.

Speaker 1:You were listening to another great podcast from Launchpad 516 Studios. You're tuning in to embrace it with Laini Anastella, brought to you by Launchpad 516 Studios. They've gone. They've spent, you know, just a shitload of money on doctors that have not helped them. They wait months for a neurologist appointment just for a neurologist to walk in there and do nothing and gaslight them which I want to get into as well. You know meaning dismissing their symptoms, meaning, oh, that can't be CMT because you have flat feet and you don't have high-ash feet Just uninformed, dismissive doctors. And they come back fresh and it discourages them from pursuing additional care without those resources, without that privilege. Where should they start so that they're not, they don't run the risk of burnout and overwhelm, but at the same time, they're moving towards advocating for better care and, you know, quality of life.

Speaker 4:Yeah. So one of the things, one part of my advocacy journey for advocating for chronically ill, chronic pain, disabled folks, is the fact that if I am having all this trouble and I have all the tools, then it is harder for other people, and so gaslighting is definitely one of those things. So that's what I'm saying understanding your power, your privilege, understanding your identity, your intersectionality. So again, when I go into, like you know, when I was initially looking for my cardiologist, I was assigned one. So my primary care, my internist, she actually does Run Point on my team. I hate to use sports terms, but she's the person in basketball who has the ball. She, you know, similar to like Steph Curry.

Speaker 3:You have a good one. You have a good one I do.

Speaker 4:But that's because another thing is to say no to doctors. If they aren't serving you, you don't have to see them. There's so many of them. Go somewhere else, right. But I was believed from the beginning. So I found a cardiologist that had the same type of energy as her was believed, but I'm also me. So I did talk to other cardiologists to figure stuff out. I had one cardiologist who was like, yeah, let's just do ablation, burn electrodes in my heart, which is not smart. I was like I don't have a diagnosis, so why would you go in and burn? That doesn't make any sense. Right To do that anyway. That's all to say. I did my due diligence, even with the cardiologist I'm with now to continually work through. But those two people because they believed me, it helped with figuring out the other stuff to get to the diagnosis of EDS.

Speaker 4:I've had that same thing with a neurologist being gaslit. I'm like I have pain in my leg. What is this pain in my leg? I now know it's EDS, but he was a horrible gaslighter. So I told him that you are a waste of my time and I will not see you again. I never saw another neurologist after that, but it gave me the energy to go and do stuff.

Speaker 4:So what is medical gaslighting? Medical gaslighting is you're fine. I don't know where this pain is coming from, and maybe you're thinking you have this pain, but maybe it's not. Or maybe you should just stretch more, or have you tried low-trend or heavy-propan, or maybe you should minimize your stress, not realizing that there's things that are going on and not real. So a medical gaslighter is the person who's telling you yes, you were not an expert of your body. I've been in this body for 40 years. I understand my body better than any doctor. I need them to use their expertise, their privilege, their power to make my body feel as good as it can feel amongst my rare disease and amongst my disability. When they don't see any part of you, that's where you're gaslit. That's usually the person when you're saying can you notate in the chart that you don't wanna do that type of thing? If you leave an appointment and you're angry, you're frustrated, you're crying, you're getting gaslit because your pain is real.

Speaker 4:Now, systemically, going back into intersectionality and how people view themselves, the data is not there for you, potentially. So I've had an appointment where someone was quoting data and I followed up with them and I was like, out of the data you quoted, can you tell me the N for black women in that study, the average number? She got very upset with me because I held her accountable. So what of that study? Is this study just white men? Because then my symptoms who's finding my symptoms right? How do you know that? Have you worked with someone who has things like me, Like asking these types of questions? To get to the facts, that also can lead to gaslighting. But when the research doesn't show, or the research isn't there or it's limited, that also is harder to diagnose. So if you have something happening on your skin and you have a deeper complexion, it may look like something else.

Speaker 4:As a woman, a heart attack sometimes for me can be stomach pain, but that's not the same for men, but data is specific to men. So then it's probably just like I hate something bad, like maybe you have heartburn or whatever. It is Not that it could be an actual TIA stroke heart attack. Something is happening cardiovascularly. So those systems also go against us and add to gaslighting.

Speaker 4:I mentioned pain. Black people are not believed to be in pain. Black women aren't believed to be in pain, which is why we have a high maternal fetal mortality rate in US. It's also why pain for black people is not believed in general. It stems from enslavement of black people in this country. So to justify harm, maiming, rape, abuse and death for black people, they could take it. It's a pain tolerance for all of those horrific, horrible things, so you can't be in pain. That is taught in our medical education. That's there. The reason why gynecological care is the way it is is there is a particular doctor who would test things on black women without anesthesia but would for white women and would take enslaved people to test things out. So all the way down to the speculum that goes in those who have those parts, that comes and folds and baked into the education in which providers receive Right, oh my gosh.

Speaker 3:So yeah, yeah, I'm just I'm so many of the things that you're saying I have never heard before, which is you know? I'm so educated, I'm so so educated and whatnot, but I have never heard about black people having like the assumption of a higher pain tolerance, like that is the first time I've ever heard that and, yeah, I would encourage people to look into that Right.

Speaker 4:There's a lot of that Pretty late in general. Yeah, to advocate, or if you you know you identify as black or intersectionality of whatever black means for you. But you could just start by looking at Dr Mary and Sims. He is the person who did that Right. So things that are still using gynecological care today came from him and his inventions. But it's all around fistulas and fistulas are incredibly painful. It's tied to like pregnancy and how he was trying to adjust fistulas. But looking to that, you can see how it shows up.

Speaker 3:But it's the very reason why my, my, my big takeaway well, I have lots of takeaways that are of interest that I'm going to follow up on, but for people who are listening, if I don't know in yours instead of his dialogue, I think it's important question to ask any doctor if whatever you have is how many people have you seen, how many women for me, how many Ashkenazi Jewish women have you seen with sharp hermary tooth, right, exactly. So that's like the lesson. It's like you know, I listened to a ton of podcasts about hormones and like this functional medicine and blah, blah, blah. So, to sum it up, what I got from learning about that is that traditional medicine, as you said, their studies are based on a average, and I am using air quotes in average. So when we talk about hormones, the studies are based on the average American woman which is a size 14, which is blah, blah, blah. I am not that person, so that medical evidence doesn't necessarily apply to me.

Speaker 3:So, people, your lesson is whenever you see any physician, one question to ask is to think about you and yourself and what kinds of inherited things you may have yourself, what you bring to the table obviously, your race, your, you know, inherited diseases, whatever, and to say can you tell me not in a confrontational way but in a true, like you're interviewing a doctor, inquisitive yeah, an interviewist you're a good fit or you're not. That doesn't mean they're a bad doctor, but they are necessarily a good fit for you. If they've never seen for me an Ashkenazi Jewish woman in her fifties Sorry, I can't see you anymore and especially with Charcot-Murray-Tooth and other damage syndrome, how many patients do you see?

Speaker 4:Okay, or actually I would say do you know what it is? Yeah, that's important too. Yeah, I had a procedure yesterday actually and I was being, you know, intake. I had to go under for this biopsy. Second, I had to go under for it and the nurse that was doing my intake was asking I told her I have heart conditions, I have four heart conditions and I have Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. And she was like, well, what is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome? And you know, because I can obviously see this puzzling look, I'm like do you know what it is? And I have to educate.

Speaker 4:She freaked out how can I be going under? How can I be having this procedure done? She kept coming in multiple times about like, okay, but your blood pressure is low, yeah, I have orthostatic hypertension, I have low blood pressure, that's normal for me. Okay, but EDS means okay, but do you have chest pain? I'm always in chest pain, I have chest pain every day. Okay, but do you have? You know? Like all of these things were popping up and I was like this is my doctor. She's done several procedures on me, she knows all these things, we're good, we're good, we're fine. And then she never came back. She sent it another nurse.

Speaker 1:Yeah, and I think you know, what really stands out to me is, like you said, does your doctor believe you? And on top of that, I think the gaslighting also includes oh yeah, you have pain, but there's nothing we can do about that. Or, yes, you're having this, but that's just part of the disease and there's nothing we can do to alleviate that. I feel like that is such a hopeless place to be for a patient and I want to remind people that that is not the case, even if it's something progressive like CMT, you know, because that's my lived experience.

Speaker 1:Yeah, there is no cure, but there's a shit ton of things I can do to help myself. I can exercise, I can eat right, I can meditate, I can sleep well, I can take vitamins, supplements I can do all of these things. So when a doctor tells you there's nothing you can do about it, I encourage people to push back and maybe it's not vocally in that conversation and starting an argument with your doctor, but know that of course, there are things that we have the power to do in our lives. You know, with maybe that research, maybe with their support of an organization like HNAP or whatever. You know your disease or chronic illness is to connect with community and to find other options for improving your health. Can you talk a little bit about because I know you're big on community obviously you were a speaker at Chronic Con. Can you speak to the importance of what your experience has been with connecting with the disability and chronic illness community and how that has supported you throughout this journey?

Speaker 4:It has been a wonderful journey to being community with people who have a disability, chronic illness or disease. It is one of the most refreshing things in the world to just joke about how healthcare sucks or how you have this new pain thing or you have to wear this new brace, and I've been able to develop rich and important relationships. But it's also realizing that there is a range of what disability looks like too, and that ableism isn't just from non-disabled people, it's also from disabled people as well, so I can be viewed completely differently than someone else, right, and what that looks like, and so that's been interesting to see how that plays out in certain spaces. It's also been interesting to see how again, I have multiple points of intersectionality here that I do think about from time to time what it would be like if I were a white woman navigating this right because my pain would be believed, and how I can hear that through some stories of however I'm participating at ChronicCon or in a certain space or in conversations I may have with folks who live with disability or chronic illness, or how they were able to get to diagnosis sooner or whatever. That may be Right. So that's another side that comes from the community aspect.

Speaker 4:But I was diagnosed with officially diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in May of 2021. And again, I've had it all my life. In May is Ehlers-Danlos Awareness Month, so I was like, wow, this is great. This is very unbranded for me and you know Instagram posts that I had this thing and did it in May.

Speaker 3:Post the zebra, the zebra is the symbol of people of Ehlers-Danlos.

Speaker 4:Yeah, it's the zebra. And I mean it's because people don't necessarily see us. They aren't looking for the zebra, they're looking for the thing they're traditionally taught, right Again, that example that I told you yesterday. It's like she literally wrote down EDS, what is the thing that you have? Like I feel like she went to go Google, you know, and like figure that out, which is fine, like there's nothing wrong with it.

Speaker 4:But within community, I'm able to see how much it sucks for other people. Right, if I have rare disease, so Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is rare disease, but it's even rare for me because there's very little about what that means for black people, black women. So it's even harder for me to be diagnosed, it's even harder for me to be seen and validated. But I've been championing, I've been talking about it, I've been educating and I'm proud to say this Sunday to fly to Ireland to be the keynote speaker for the Ehlers-Danlos Society to talk about what we're talking about today, so inequities in health and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorder, which they're tied together around this disease, and I was able to do that. You know it's 2023 and two years, and so I don't plan on stopping on having that advocacy. I'm excited to be in community with folks you know in another space, but it is a bittersweet. It's a bittersweet thing to be in community with people with disability and chronic illness.

Speaker 1:Especially when you're the rare advocate or the first to break some of those glass ceilings. It's yeah, it requires all that much more energy.

Speaker 3:I feel like we've only covered just a little tiny bit of you and all that you can teach us. I had told Estella before this podcast started. I'm like do you know that she edits books for those books to make sure and I don't know what the terminology would be like that you've written that you haven't said anything about sensitive.

Speaker 4:Sensitivity editor. Sensitivity editor yeah.

Speaker 3:I think that's like the coolest thing, right, Like for all of us. Like we don't even realize we're being offensive in the way we communicate and write. Some terms change. Everything is changing all the time.

Speaker 3:You know, I was actually listening to the and this is a side note, maybe you won't even include this, but I was listening to our like my local Detroit news and I'm like I'm from Detroit. Well, yeah, yeah, so I'm from Detroit. So I was listening to one of the newscasters and she's a black woman and she's beautiful and she uses African American all the time in her talk. But then I'm like, okay, well, that's have what I grew up saying, but is it one of those things that she can say it? But I can't. And I should say like, like, even as a person who is educated like myself in this world of inclusivity, I'm like not even sure. So I was listening to that and I don't like I'm not saying that we should talk about that, but that's why I can give you the quick synopsis they're, they're, they're fine, I I choose to say that I'm black.

Speaker 4:Black is more inclusive of people who identify as black. If someone says they're African American, call them African American. I'm not African American, I'm Haitian American, so I don't identify as African American, right, and so black. Two years ago, we started capitalizing black, and that's because black is a group of people, it's a community, it's a culture. We don't capitalize white because it's not that, but that's what black is, because there's so many points of intersectionality there.

Speaker 4:A lot of it stems from the fact that there's a history of enslavement in this country too, so lots of people are coming from lots of different places. I say that, and I say this in my book too, that I am the transatlantic slave trade, so my identity literally comes from. You may know it as like the slave triangle when you were in school or whatever, but it means that my identity stems from Europe. Thank you, haiti. And my particular port was New Orleans, right, and that is. That is who I am. That makes up my identity, and so I Grew up as a first-generation person, my father's Haitian. Sometimes I forget that I'm, unfortunately, an American. I get mad at Americans, but no, that's you, I'm.

Speaker 4:American too, but I grew up like a, like an immigrant here in this country. That also goes back to my ununprivileged. My father knew from his privilege that he had growing here that I would have more of an opportunity To grow and to flourish. But it also is why I have so many degrees, because in my particular family and culture you have to have a minimum of a master's degree. I knew that at nine years old, again tapping back into my privilege. So there's nothing wrong with saying either of them, it's just realizing. People identify how they want to identify and we support how they want to be identified. Same for pronouns, right.

Speaker 3:Yeah, I don't mean to cut you up like. I have a child who became trans in their 20 at University of Michigan, right, so I understand about like asking people what they want to be called. However, as a white woman, when I describe people, a lot of times appearance comes into the equation and I feel like we tiptoe around appearance saying like oh, there's Laney. Like if someone she has long dark hair, she's whatever, and she's white, light-skinned, like I sometimes don't know what is okay. Like I mean, that's Things are we changing is beautiful. She has a big smile. She has darker skin than me. Yeah, I know, I mean I.

Speaker 4:I publicly identify as black. So you know I'm openly black. I've been openly black for 40 years now. So People can say that I'm black and there's nothing.

Speaker 4:There's nothing wrong with that right. But if you look at the descriptors on Instagram, I don't say that I'm black. That's not part of my descriptors. Other descriptors will say that and that's because it comes through and what I'm talking about as black people we us and how we advocate people, can you know? Pick it up. So there's really no wrong way of doing it. It's just. As someone identifies differently, we correct it for ourselves and identify them this way. I can describe myself right now as a Person who has curly hair, that's, you know, on the top of their head, with blue frame glasses, you know, a big smile, as you said, wearing an Oakland roots gray sweater, sitting in front of a bookshelf. Right, that's explaining me as the person. But someone may say all those things and add a Black woman with a caramel skin tone sitting, you know, and both of those things are fine. It's just keep in mind, when white people are described, skin tone doesn't come up. So it's that person over there with a hat. It's a black person.

Speaker 4:It's the black person over there with a hat, right Uh-huh. And that is also how whites privacy works, right?

Speaker 3:So if we're describing people equally in the same, we would do that adding captions to descriptions, descriptions that I would say, like if a cell is a Latino woman but let's say she wasn't, I feel like I would say she's, you know, a caramel dark. You know I would skinned woman like, and yeah, anyways, this is so. You're so interesting.

Speaker 4:I do. I do what I can. I just don't like to be bored, so you know.

Speaker 1:That's for sure. We're definitely not bored, and I'm sure our listeners are not bored either. But you, you did mention you have a book coming out, is that correct?

Speaker 4:Yeah, so I'm lucky enough to have a book deal with a top five publisher has shut and my book comes out February 2024. I wrote it myself. I like to put that out there because there are ghost writers. A lot of people don't realize that that's a whole profitable industry. But the book is white, supremacy is all around.

Speaker 4:Notes from a black, disabled woman in a white world. It's a play on love actually, if anyone knows anything about love actually. So if you watch that oh you know, classic holiday movie of like a hundred thousand times, yeah, yeah. So the first, that movie is, like, you know, the airport or the airport not spoiling anything for anyone who hasn't seen it, but it's a reminder. At the airport you can see that love is all around. Like you know, people miss someone, someone's coming back. They're happy, they're there, they're happy, they're home, right. It's the same thing for white supremacy it is all around. It is all around.

Speaker 4:So I talk about my lived experience, my stories are shared in the book and so for people who look and live like me structurally, however they identify with one or multiple things that I identify with, they can feel validated, seen, heard, maybe even get some advice. And for white people who have been doing the work since the murder of George Floyd, may 25th 2020. They can apply what they've been learning and read those stories and see systemic racism, see oppression, see discrimination, see ableism and those stories Applying what they've learned, moving past allyship and further moving into to being Um and accomplice. So that's what the book is all about. Um, you can google it. There's a pre-seller link that's out there. If you want to pick it up, um, I would appreciate it because you're supporting a black author, a woman author. I just able to author the tribe.

Speaker 3:Maybe we need to be willing to come back on at some point because I like, I feel like, like I said, there's so much and now with the book we can, when it is out there. I know that would be.

Speaker 4:Absolutely I'd be happy to come back and I think it's important to note that I pushed really hard to have myself with the cane on the cover, because I wanted people to see disability, I wanted people to see beauty and I wanted to see how that literally makes my existence hard. It's not hard to be a woman. It's not hard to be black. It's not hard to be disabled. Society system structures of white supremacy make it. It's challenging, they make it almost unbearable some days, um, and so I wanted to make sure that there was representation for my disabled community, um, on this book cover and I'm proud to say it looks pretty great.

Speaker 1:Oh, we can't wait to see it, we can't wait to read it. We'll definitely include the links in our show notes. And I think, to kind of wrap up this conversation, I, we, we both got so much out of it and it was just a pleasure having you on Um. But at the beginning of the conversation you, before we started recording, you mentioned something, salami, about Kind of celebrating the, the little wins and celebrating ourselves. Can you kind of reiterate?

Speaker 4:that? Yeah, absolutely so. Um, right now, as we record its disability pride month and it's a big month and source of pride To to be disabled and does that mean, again, these systems are not designed for us, the art, environments aren't designed for us, uh, people's attitudes, behaviors, thoughts and beliefs are not designed for us, and so that's something to really highlight and celebrate in july, but also every month. So if you live, uh, with disability, chronic illness, disease, I have major depressive disorder, mental health stuff going on Um, if you got out of bed, that's fantastic. If you brush your teeth, oh my god, incredible, amazing, right? So whatever your body is doing for you that day and whatever you're still able to accomplish, you should celebrate that.

Speaker 4:And so I celebrate Little things every day. I find little pockets of joy every day, and for me, that may look like being able to take a bath. When I bought my home, the first thing I bought was a whirlpool tub, so that's something that gives my body, you know, relief. So being able to be in the tub is like, oh my god, like it's incredible and amazing, if I have the time to do that sometimes, and don't have the time to do that, meaning my body doesn't feel like it or I'm traveling too much. Whether it's a mini brownie or a capri stun or something you eat, that thing.

Speaker 3:I love that you say a mini brownie. You said this yeah, I'm like thinking, I mean you can have more than a mini brownie people if you want like a big brownie. Eat a big brownie. Or 20 dark chocolate eggs, like I did.

Speaker 4:It's currently hard for me to eat, so for a mini brownie is like a big thing, but yeah, but when it's not a hard time to eat, it's free. It's three of the mini brownies, which makes a full-size brownie. There's ice cream on top. Right now it's like a little mini brownie and a little bit of like almond milk and that's like my exciting thing that I'm able to do.

Speaker 4:But it's important to realize that you are nothing short of amazing. So my tagline how I sign emails, I, what's on my t-shirts I have it's keeping amazing and that's what you do every single day, like, whether you know it's as simple as getting out of bed or, you know, getting that appointment. We are designed to not be amazing because of these systems and structures. Yet here we are. We're talking on this podcast, we're showing up every day, hey, we're defying the odds for non-disabled people, or whatever they think, but we ourselves are nothing short of amazing for navigating in pain, discomfort, um, in a world that doesn't necessarily value us. So that's why you should celebrate the little wins, find pockets of joy and keeping amazing.

Speaker 3:Yes, you are amazing and all of you are amazing. So, lastly, how can people find you? We are going to include this in the show notes, but if they want to start following you and get your little tidbit, so yeah, but not where would they go?

Speaker 4:Yeah, so I'm. All platforms, including drugs, at change today. So ch A, n, g, e, c, a, d, e, t. So today, like cadet and find me there. That's also the same for the website, um. You can find out more about book on the website. You can buy a shirt on the website, um. Or, you know, slide on my dms, it's me. I will happily tell you you're amazing or commiserate with you or Um. I'm always happy to navigate about health stuff, um, you know, if, if that's what someone wants, um, I am available as long as my body allows me to do it. Um, and it's also the same for, like, white pharmacy stuff. You have questions around diversity or how you're navigating that for you or other people, the work you're on, or how you're advocating for yourself. I'm always happy to do that. I have boundaries, so it may take a while for me to get back to you, but I will get back to you.

Speaker 1:Thank you so much. You are amazing. And we can't wait to see what you do next and um best of luck in Ireland and Um the rest of the year when we look forward to seeing you back, and it was so cool meeting you.

Speaker 3:You gave me lots of food for thought, so I'm going to go do my homework. I'm gonna have to and then and then eat my mini brownie and then maybe another three.

Speaker 4:One big one, yeah, whatever I want to do.

Speaker 3:I'm celebrating me.

Speaker 4:You are yes, absolutely, thank you. Thank you so much.

Speaker 1:Take everyone Thank you. Hey, embracers, thank you so much for listening and supporting the embrace it podcast brought to you by launchpad 516 studios Executive, produced by george andriabolos and hosted by lanie ishpia and distella we go. Our music and sound effects are licensed through epidemic sound embrace. It is hosted with bus sprout. Do you have a disability related topic you'd love for us?

Speaker 3:to feature, or could someone you know be a fabulous guest on our show? We would love to hear your comments and feature them on our next podcast, so leave us a voicemail or you can even send us a text to 631-517-0066. Make sure to subscribe to this feed wherever podcasts are available and leave us a five star review on apple podcast.

Speaker 1:While you're at it, follow us at embrace it. Underscore podcast on instagram and make sure to follow all the great podcasts produced by launchpad 516 studios. We hope you join us next time, thank you.

Speaker 3:We hope you join us next time and continue to embrace it.